I keep trying to remember the first time I heard Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ voice. Technically, I read it. And that was definitely in the Black Twitter era. Maybe it seems random to start with the voice of a writer, but I want to focus on her voice because hers is among the most distinctive in American letters to me, particularly at this moment.

Miss Jeffers’ voice is an unapologetically Black Southern womanist voice, authentically and generously paying homage to African-American ancestral lineage, to Black women and to Black Southern culture, which is the foundation of American culture. The first time I heard her by reading her words, I knew that she loved Black people because of what she wrote and how she wrote it; the ferocity of her defense of us, because she would tell the truth, and then she would tell off the people who tried to come for her as soon as they did with more truth. If I’m being honest, I was a little afraid I might misstep, and I’m pretty sure I did when I forgot the accent in her first name during one of our early exchanges online — a mistake I would never make again.

So there is that gravitas, that energy like a whirlwind with language, that I love when I read her. But the honesty and beauty in Miss Jeffers’ voice that I admire most is that it sounds like home. Like fellowship. Reading her writing gives me the feeling of talking to my friends on the phone for hours that pass like minutes or talking mess across a kitchen table over a delicious meal: Manna. Though I have never met her in person and only rarely have heard her actual speaking voice, I was an early fan of The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois — the most sweeping epic of Black life and legacy I have ever read and probably ever will.

For someone who has struggled to find and identify home, with just a handful of people I consider genuine friends and family, locating the comfort and peace in an author to whom I am not related is an uncommon experience. But I wonder if some of the ethereal magic of Miss Jeffers’ pen is that she makes everyone feel centered, like she is talking just to you.

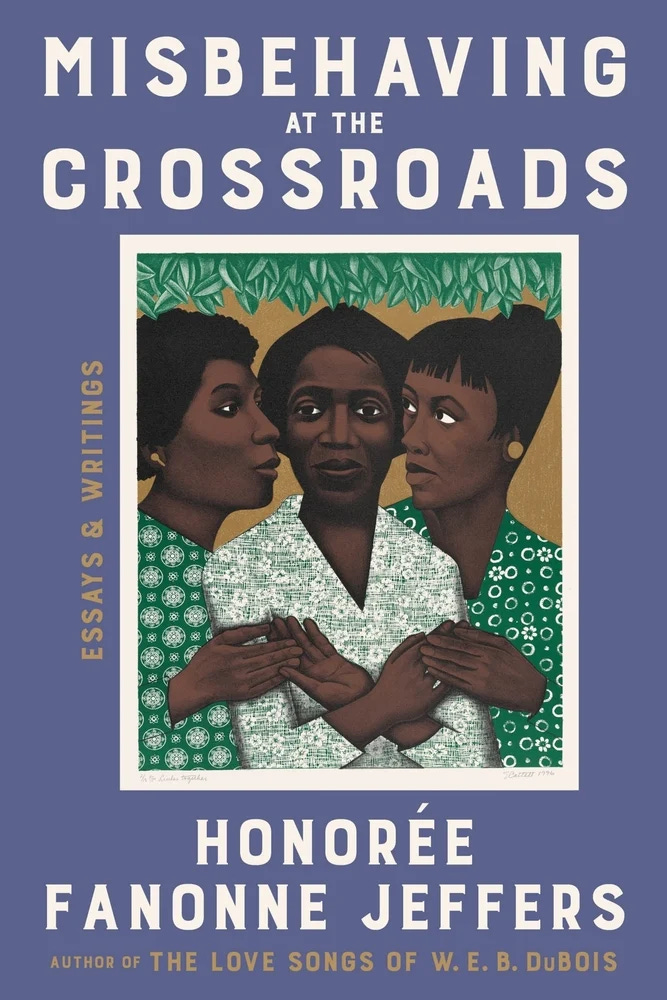

Misbehaving at the Crossroads, scheduled to be published June 24th, is a treatise that combines memoir, poetry and essays in a way that hasn’t resonated with me since I found Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, the collection in which Miss Walker defines womanism, articulates a Black womanist creative sensibility and locates activism for Black women in our everyday lives unlike any other writer has ever done. Misbehaving at the Crossroads is certainly in the tradition of Miss Walker’s work, and as a collection, poetically continues the conversations Miss Walker started decades ago, bringing reflections on the ways Black women continue to navigate autonomy, community and resilience into the modern era.

I highlighted large swaths of my galley, because I found so much truth ringing in my ears that I wanted to be sure to capture it all. I can’t wedge it all in here, but I’ll start at the beginning, with this assertion from the perspective of January 6th apologists and their ilk: “Nobody BIPOC can be right, unless they agree that Whiteness is the logical conduit to moral and political authority in the United States.” I wish that attitude was older and less relevant than it is, but I still appreciate the clarity and insight, as much as I detest this truth.

In the essay that follows, “Our Fathers Who Rewrote Our Mothers,” I was fascinated to learn about the legal and social context of Black mothers during enslavement and how it carried forward into ongoing slander in the centuries to come. I’ll be giving birth to my first child soon, which I’ve been writing about, and so I was struck by seeing in Miss Jeffers’ pages a phrase that I’ve seen in other places: “Partus sequitur ventrem, which translates to ‘Offspring follows belly,’ a barnyard term, given to the breeding of horses and cows and pigs and dogs. This is how colonial White men viewed Black women: animals grunting and shitting in a field.”

I also learned how this damning status came to be applied to Black women in America, through the freedom quest of Elizabeth Key, whose mother was an enslaved Black woman and whose father was a free Anglo-Virginian. Ultimately, once she was forced to pay reparations for being enslaved (italics mine), Elizabeth got her freedom, but Virginia changed the law in 1662 to change the status of Black women’s children, so that they would “serve as the condition of the mother.” Put another way, “If the credit for founding this nation has been given to the White man, then the burden of slavery has been assigned to the Black woman. She was the inverse image of Eve, both mother and not mother, for her children didn’t belong to her.”

There’s much to unpack there, and Miss Jeffers does so, pointedly, with incisive critique. She charts a path from this brutal past through to her reflections on her family history, her status as a daughter to a hardworking, visionary mother and a predatory, abusive father; as a sister and granddaughter in the American South.

I’ve focused here on the heavier aspects of Misbehaving at the Crossroads, but there is levity and wit in the collection as there is wherever Miss Jeffers is using her voice. For instance, as triggering and annoying as Miss Jeffers’ descriptions are of her encounters with white peers in the writing world and in academia, they gave me life. There is a letter to the now-deceased white male poet who made an outrageous and crude sexual comment about her Southern accent that he should have been properly shamed for while he was alive, but karma being what it is, she at least has the last word. There’s an eviscerating “Imaginary Letter to the White Lady Professor Who Might Have Extended an Invitation to Read Poetry at Their Prestigious University” who has shown an “appalling lack of home training” on a lot of levels, including referring to Miss Jeffers by her first name, inviting her to their institution while also offering an honorarium that is “99.9 percent less than my asking fee” — an encounter that Black scholars the world over understand and will be able to relate to. (I highly suggest using this letter as a template for when you decline such invitations, because you should.)

I cannot explain the combination of embarrassment for Some People and deep glee for the Black women who give Those People grace I felt reading “Imaginary Letter to the White Lady Colleague Who Might Have Sat Next to Me at One of the Now Eliminated University Workshops for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Training.” Let me tell you something — It is a work of beauty. I hope I don’t have to explain much about the inanity of experiencing DEI training when your whole life is a clinic in trying to get others to value DEI. That’s another story for another day.

Miss Jeffers captures the truly strange expectations that well-meaning white colleagues in academia (and others who do not mean well) have of the too-few Black peers they encounter, particularly for a performance of gratitude for just breathing the same air. I was tickled by it, sad as I am for every Black woman who is expected to do “academic housekeeping” while also carrying the loads we alone are required to carry.

In one of the more personal essays, Miss Jeffers writes this, at the end: “Here I am, unrespectable and unashamed, waving from truthful territory.” And that is, honestly, the best description for everything else in Misbehaving at the Crossroads — with the exception of the unrespectable part. What I deeply admire and respect is the honesty in these words, especially: “It was hard to travel here, and even more frightening to admit that once, I was a coward. I wanted acceptance so badly that I fell in love with my own defeat.” My goodness, I have been there. I thought I was the only one. Thank God for Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ voice in this American wilderness, echoing across the centuries, to remind us that we are not the only ones trying so hard to tell the truth, trying so hard to fall in love with victory instead of defeat.

Adding this to my goodreads rn! Incredible review

Joshunda, this review is masterful! You've captured exactly why Jeffers' voice feels like fellowship. I'm struck by her line about 'falling in love with defeat' vs victory. As a father preparing my daughter for these same academic and professional spaces, I'm curious, what does 'falling in love with victory' actually look like in practice? How do we teach that transition?