“What has happened to Black people when they, their families, or their communities went mad?”

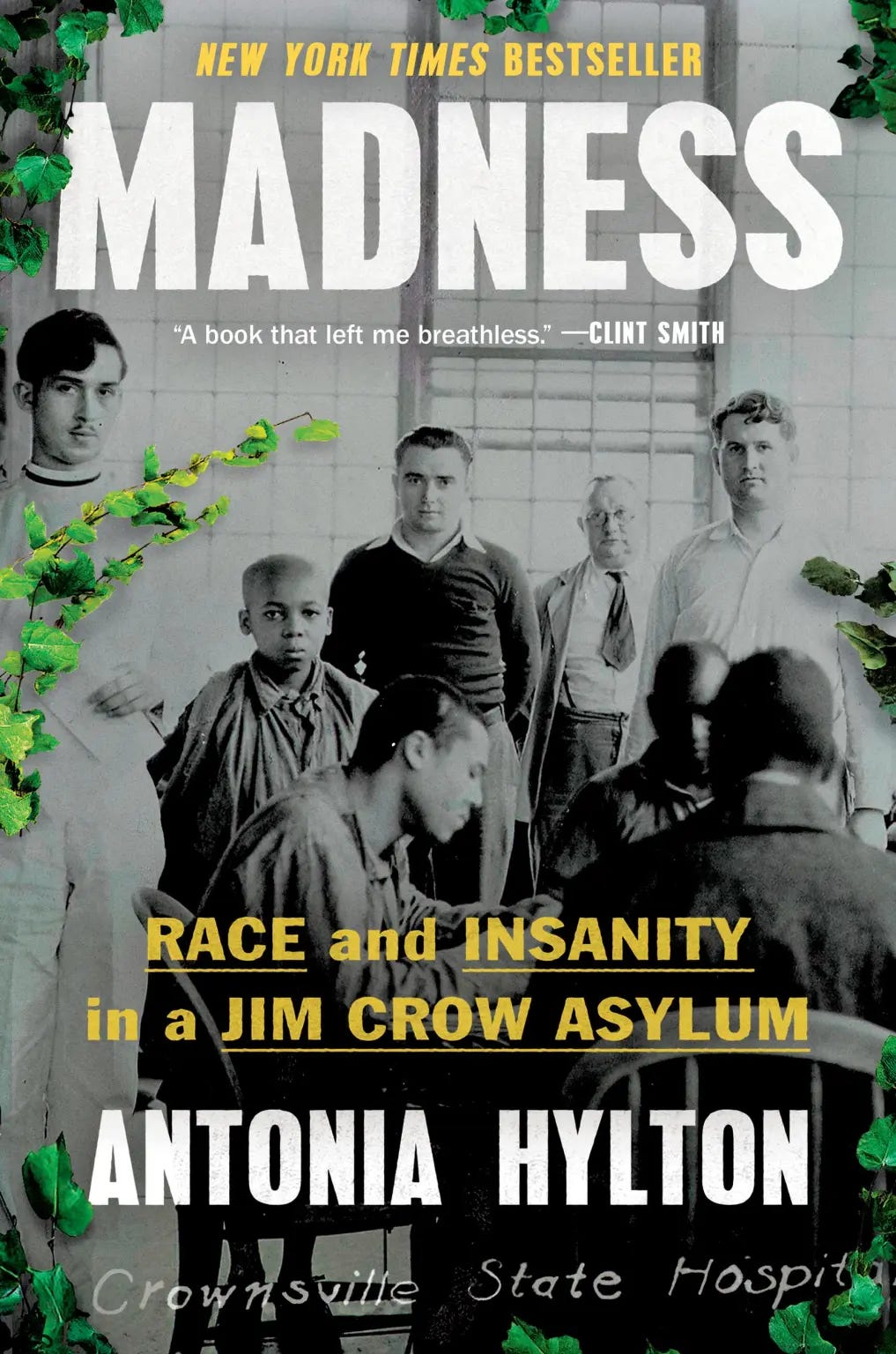

There is a way in which all of Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum, is one answer, in a list of very long, complicated possible responses, to the question that Antonia Hylton poses in the introduction. Crownsville Hospital, formerly Maryland’s Hospital for the Negro Insane, represents an intersection of common, tragic responses to mentally ill people in the Black community. The story of this depraved institution is a shameful one, with many layers.

We can start with where Antonia Hylton begins, which is when Crownsville was first built in 1911 with 12 patients before the number of patients swelled, in 1940, to 1,611. Those days not far past Reconstruction found our country making up stories that originated in the pro-slavery propaganda of drapetomania, that there was something mentally wrong with Black people who ran, who wanted freedom, who did not know our place.

So Crownsville becomes a place where mentally ill Black folks are subjected to “industrial therapy” and the term “patient labor” — apparently popular around the world — becomes justification for making the beloved relatives of families who don’t even know how to begin to talk about mental health victims of their own diseases.

In later years, this exploitation takes the form of criminalizing those who are most virulent and out spoken on the topic Black power, because of course it would. But heartbreakingly, we can see the impact of an institution that reinforces the racist belief that all Black people are a little crazy, or at least crazy enough to throw behind the gates of an underfunded, cheaply run asylum — even when those admitted to Crownsville have been kinfolk of our pillars of American history.

I’m thinking of the story of William Murray, father to the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray, activist, author, poet and lawyer, who is one of the first to die from injuries inflicted on him by staff at the hospital, but certainly would not be the last. By including the father of a legend in the uncovered stories she presents, Antonia illuminates that regardless of class or status in the community, each patient who went to Crownsville was subjected to whatever often fatal destiny awaited them, simply because they were unwell.

Those of us who have had mental illness touch our lives personally know well that the interaction Black folks have with institutions is forever warped by the racism that is a part of the architecture of every system and structure in America. Because mental illness is a chemical affliction, it is particularly susceptible to manipulation by others in service of their biases. I know this because I knew mental illness intimately as a child and young woman.

Antonia puts it this way:

“Without having the tools or the language to talk about it, I became aware of something early: our traumas and illnesses are frequently intertwined with American history and the peculiar reality of being Black. And at times, our traumas would be compounded and exacerbated by poor, discriminatory, or nonexistent treatment when we needed support the most.”

I was drawn to this book because bipolar and borderline personality disorder are part of my family line. I have been told that my grandmother on my mother’s side died in a mental institution when my mother was thirteen. Reading Madness, in all it’s brutal, tragic and finally, because of the work of Antonia Hylton, now-legible history, my heart broke again thinking of what my ancestors had to endure because of systems in this country that refused them the compassion and empathy every citizen deserves. It made me wonder what other atrocious histories have yet to be told because we refuse to look at their ugliness, and what their existence means about us.

Beautiful review. I just finished this book and have been sitting on it for awhile. It’s hard to put into words how impactful this book is.

I purchased this book when it came out but haven't read it yet. I know it will be a hard--but necessary--read. Your comment from the book about all Black people being a little crazy made me think of Drapetomania, a "mental illness" that made enslaved Blacks want to escape slavery. Unbelievable. Anyway, thank you for the thoughtful review.