It takes a special kind of person to be a nurse. Given the history of healthcare in this country, and how the healthcare system has exploited, maimed and killed Black people (for more background, Harriet Washington’s Medical Apartheid, and more recently, Linda Villarosa’s Under the Skin) it takes an extraordinary faith in humanity for Black people to follow their vocations in health and healthcare. Much of my work in the world now is focused on communicating about racism as the root cause of health disparities in this country and moving the blame for what has ailed Black people away from their individual choices, shifting the blame where it belongs: With systemic racism and those who protect systems that privilege white health and wellbeing over everyone and everything else.

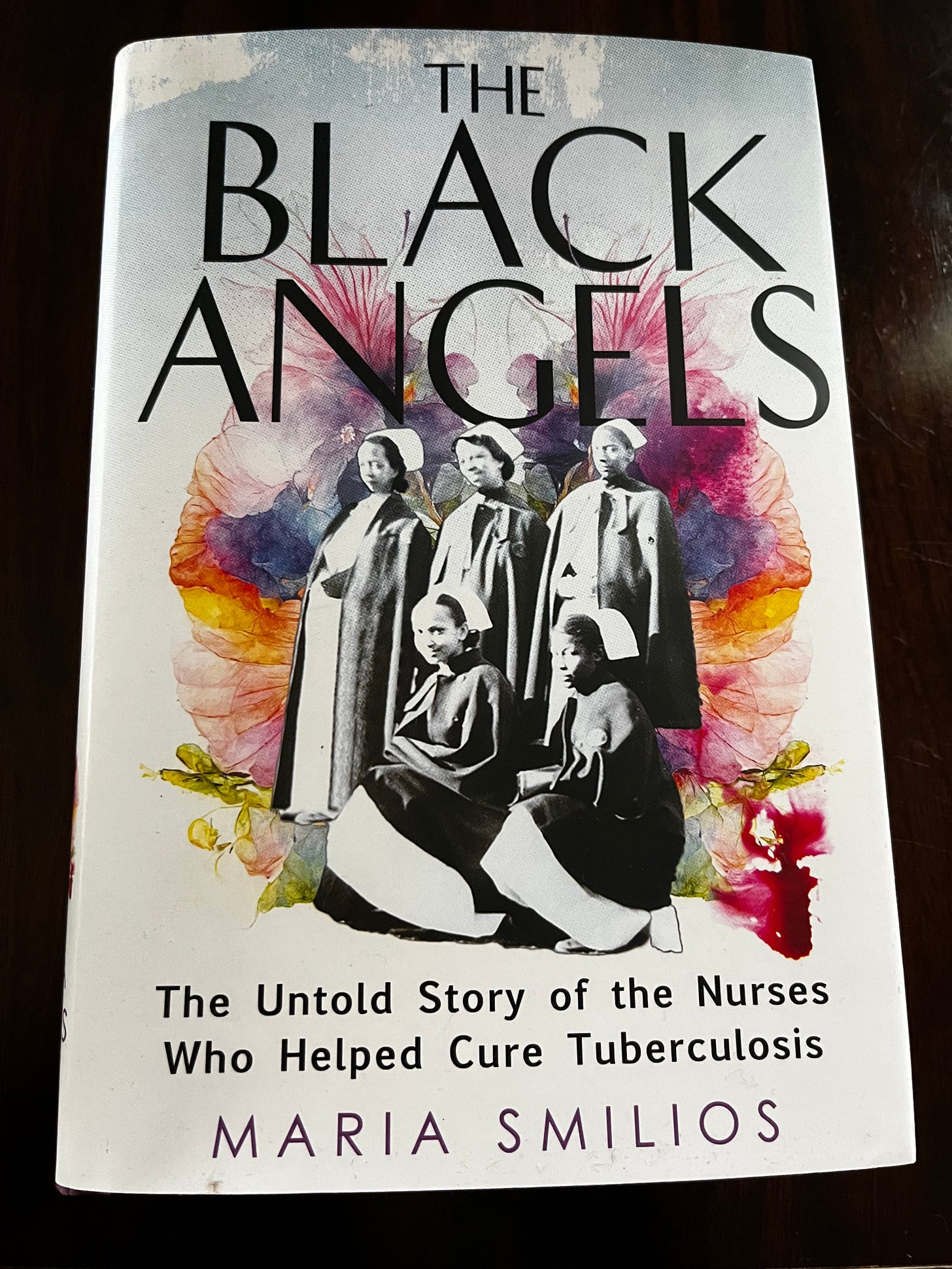

I thought about this throughout Maria Smilios’ beautiful new book, The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis. It’s an important treasure focused on the little known Black nurses during the 1940s & 50s who assisted doctors at a Staten Island municipal facility called Sea View as they discovered a cure for tuberculosis, the plague of that time that continues to have an impact around the world. White nurses were quitting so fast they couldn’t be replaced by anyone but Black nurses from the South, lured North by the promise of better, more dignified work and enough money to live.

The Black Angels opens with the story of the last surviving nurse who worked at Sea View, Virginia Allen, and with clear and novelistic prose, describes the hostility and low expectations that followed Black women who were willing to expose themselves to disease even to treat Nazi soldiers. The disrespectful treatment they endured in segregated then barely integrated hospitals and healthcare settings is tough to read, but important to remember. Racism in nursing is still very much a part of the health and healthcare system in America, and seeing its long continuum, and naming it, may eventually help us to interrupt it, maybe, I hope, eliminate it in another lifetime.

Though The Black Angels is nonfiction, it reads like historical fiction with its details of how tuberculosis was killing one in seven individuals, the patients whose lungs gave out, the ones who eventually were cured and could leave, when they thought they might be confined to a hospital bed at the end of their lives.

I wish I understood or could convey more fully why it is so important to me to learn how Black women not only overcame bigotry but also how they flourished in spite of it. Some of it has to do with being reminded of the tradition in which I try to work as a Black woman writer, this inheritance of resilience and power and patience that makes me feel that I can conquer any obstacle because my ancestors did. Some of it is that as I learn more about their stories, their struggles and their triumphs, I feel like my thriving is a defiance of the shame they had to endure.

It is sad how little our school systems teach us about the fullness of American history, and that it has taken until 2023 for me to encounter some of the truth of the lives of these pioneers. But I also feel encouraged and excited that these stories are increasingly being told. Ironically, I finished the book on the same day that 75,000 healthcare workers walked off the job in the Kaiser Permanente system. We say we want others to be well, then we treat the people who make sure that can be true as if they are dispensable. Shame on us for how we disregard the dignity of those who cure us, who extend our lives, who enable us to have better lives and more years with the ones we cherish

. The Black Angels shows the too long history of that and gives us the choice to be better now, and in the future.