Review: Neighbors and Other Stories by Diane Oliver

If you only read one of Ms. Oliver's remarkable stories, my recommendation is "Mint Juleps Not Served Here."

I am currently reading a half dozen books, which is pretty standard practice for me. But when I learned about Diane Oliver by way of Michael A. Gonzales noting how his essay led to Ms. Oliver’s reintroduction to this generation of writers in a Substack note, I left almost everything alone to focus on this quietly intense collection.

Ms. Oliver died at age 22 in a motorcycle accident days before she was about to graduate from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1966. In her short life, she published a number of beautiful short stories that have now been published in a posthumous collection, Neighbors and Other Stories.

I have one caveat about my fascination with this work and Ms. Oliver’s story in particular. There is a draw to Black death in this country, and maybe in the world. We tend to lionize Black writers when they are gone. We lift up their promise, flashing photos of them when they were young and sexy, not when they grew older and wiser, and possibly had the privilege to become our elders.

There is a way in which I can’t help but be a part of the romanticization of literary lights like James Baldwin and Toni Morrison and Audre Lorde — they lived productive, relatively long lives. And there is still a way in which we add to what they wrote and said on the record and lean on their words to fit whatever context we want. It’s a dangerous habit to be in love with the words and stories of the deceased. They can only speak back to us in their work, and they have no say in our ongoing revisions. I believe it is also a real danger that we can endlessly project our needs and desires onto the writers of the past, and maybe this is something they want, to be able to be remembered and timeless. Maybe us reading and quoting them is a way of keeping them alive.

So these are my own reflections and worries to tangle with, regarding the living and the dead. All of that said, Ms. Oliver’s work is vivid, precise and humane. She writes about the hesitations and humiliations of racism in everyday life during the Civil Rights era with a razor sharp pen. Setting short stories in the milieu of segregated America is a feat of its own, trying to write with dignity about undignified people and their undignified treatment of fellow citizens is not as easy as simply telling a Black woman’s truth. Her particular talent, then, was and is, zooming all the way in to the minutiae of what racist impatience, ignorance and intolerance feels like — for people who are Black, but also for those who are white — and making readers feel that, too. This is true, especially in a couple of my favorite stories.

“The Closet on the Top Floor” features Winifred moving in to a Southern girls’ college after her father has fought mightily for her to integrate the otherwise segregated school. You can tell a masterful writer by her opening paragraphs, so read the sense of difference as it is displayed in this one:

They were all wearing white raincoats, but hers was a kind of pale blue, making her stand out from the rest. At the time, she was too busy to worry about raincoats, trying to move her luggage from the car to the seventh floor of Wingate Hall. And she was becoming frightened, too, looking at all those white faces pressed against the windowpanes.

In a short period of time, Ms. Oliver has established so much with her economy of words. It’s probably raining. A lot of people are watching, but they’re not interested in helping, even if it is a Southern place and her room is on the seventh floor. She’s probably got roommates (boy, does she have roommates!) and they’re probably with the oglers on the first floor, hanging out while she and her parents figure this out, and work around this decidedly unwelcome scene. The beginning of this story might as well be the end.

There are similar demonstrations of the unfriendly, staring world around Ms. Oliver’s characters in stories like “The Visitor” and “Spiders Cry Without Tears.” But my absolute favorite is “Mint Juleps Not Served Here” about a quiet, peculiar little Black family that lives in a forest that is discovered every so often by an intruder, usually white, and typically with some kind of societal institution. The calm oozes through the sentences here, and the mother and father are brilliantly precise when they speak. They use words like language is a currency and they are on a budget. It’s what makes the story brilliant and eerie and memorable.

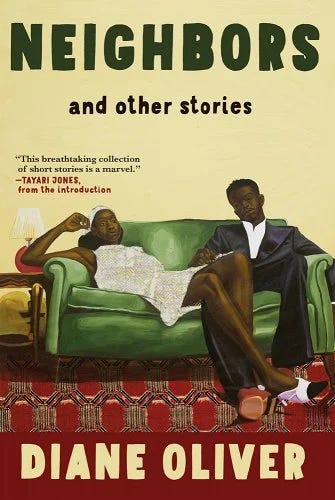

With a collection of work from a young writer, there are bound to be beautiful high points like this and some uneven moments. I don’t think it’s worth pointing them out; I only value constructive critique when it is delivered about my work, so I try to offer that back to the world. But I have no doubt that with further revision, Ms. Oliver’s other stories would have soared and won her much acclaim. Kudos, too, to the folks at Grove Press who chose the beautiful work of Cornelius Annor to grace the cover. I had never heard of him or seen his jubilant work, but I can’t think of a better, more fitting visual introduction to this collection.

I love this paragraph, because it’s so true: I have one caveat about my fascination with this work and Ms. Oliver’s story in particular. There is a draw to Black death in this country, and maybe in the world. We tend to lionize Black writers when they are gone. We lift up their promise, flashing photos of them when they were young and sexy, not when they grew older and wiser, and possibly had the privilege to become our elders.

Great post!