Like so many people, I have a special relationship with the color blue.

I never learned to ride a bike because during a short stint in foster care as a five-year-old, I refused pink, the offensive-to-me-then color of the girly bike my foster mother insisted on. Blue was for boys back then, and I understood it, but I was (am) a Batman fan, and the deeper, more midnight the blue, the better. Pink or no bike, she said, so we left Sears without a bike for Joshunda. Being the Capricorn I am, I was good with that even as a little girl, because stubborn shouldn’t always win, but it was pretty much all I had that was mine.

A few decades later, when I thought I would never have a loving ceremony or a partnership worthy of celebration, I married my love in a royal blue dress I scored on sale at Macy’s. We exchanged vows under a turbulent turquoise sky threatening rain over a majestic beach. The clouds parted as I sang “Ribbon in the Sky,” and the sun shined on us for a bit as we reveled in each other and dipped our toes in that wide beautiful Atlantic.

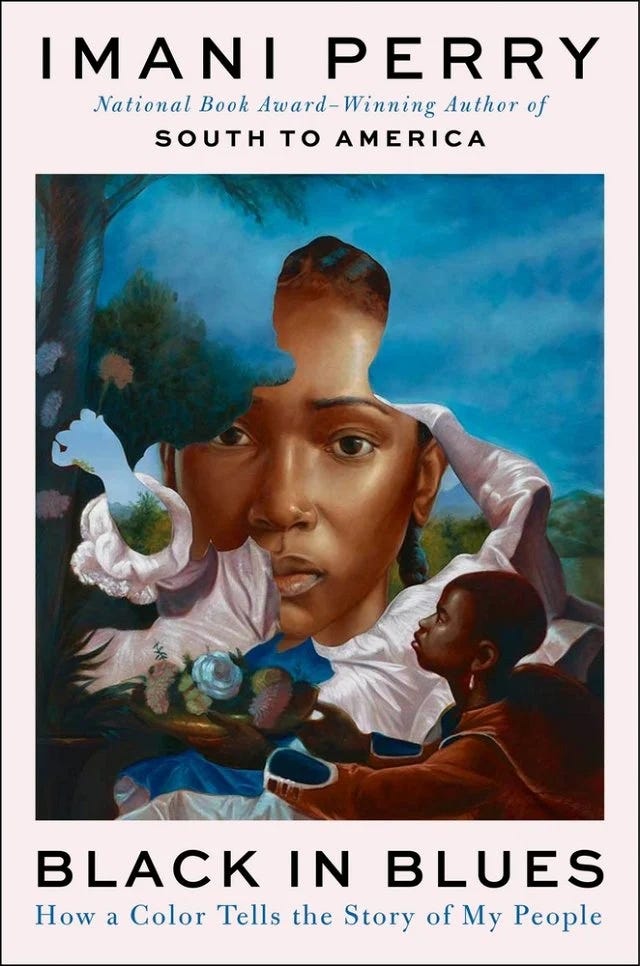

I had not thought about these two stories until I was almost done with Imani Perry’s beautiful latest book, Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People. Her book is characteristically evocative, educational, thought-provoking, challenging and lush. It was, for me, the kind of reading experience I believe readers look forward to the most — you get to see yourself in pages that outline a specific way of seeing, to respond with memories and reflections of your own related to the text.

The book covers blues as music, as art, as a way of being, as a whole mood throughout history. Blue-black skin, blue gums, true blue as dependable honesty and True Blue, the slave ship trafficking indigo and enslaved Black people — it’s all here. How, I wondered, would Dr. Imani Perry tie all of these things together in her graceful, grace-filled way? Notice I did not ask “if” — one of the promises of a master writer is that you know you will be treated to beauty, even if you are not sure what form the beauty will take.

One form beauty takes in Black in Blues is a catalog of memory and remembrance:

One of the remedies we who study Black life have pursued is diligent recovery in the face of being forgotten, obscured, or submerged. We piece together clues and uncover hidden stories. This work is important because the work of remembering is also the work of asserting value to what and who is remembered.

Another is the delight of an educator’s revelation, at least to me/this reader, of a fact I wish I knew a long time ago, such as George Washington Carver’s innovativeness in re-creating a rare Egyptian blue he called Oxidation #9:

It caused an immediate sensation. By detailing the oxidation number and process, Carver showed the world how to replicate a color that had been cherished two thousand plus years prior. But no one in the Western world had yet been known to re-create it precisely until George Washington Carver. Representatives from paint companies excitedly trekked to Tuskegee, Alabama, to purchase his formula for Egyptian blue, along with his other paints, including a striking version of Prussian blue. And as is common in such stories, Carver does not appear to have been fairly compensated for his innovation. But that didn’t dissuade his constant innovation. He was driven by beauty and care rather than accumulation. He described the things that money could not buy as the “imperishables” and treasured them accordingly.

There is more to discover in Dr. Perry’s own words, in a little over 240 pages, including some glorious photographs of blue artifacts and artwork she describes in essays throughout. So I won’t quote half the book here, though I’d like to. I’ll leave you with one of my other favorite highlighted passages though, and you should go buy her book and read the other clean, resonant sentences for yourself:

We — the people who encounter the beauty of an artist’s work — are also experiencing labor, process, and memory; we are part of their transformation and transposing of our relationship to the past. Frequently, Black people speak of being haunted by the past: slavery, conquest, Jim Crow, colonialism. But the artists teach us people of today to haunt the past, to whisper to the ancestors and rearrange the materiality of their lives with our care, to show them they are respected and loved. A haunt is a place we frequent. To haunt is to trouble or frequent somewhere. We haunt the past to refuse to let it lie comfortably as it was. We give back to them in return for the inheritances they have bestowed upon us.

Sounds deliciously true blue (as dependable honesty). You/Dr. Imani Perry had me at ". . . the artists teach us people of today to haunt the past, to whisper to the ancestors and rearrange the materiality of their lives with our care, to show them they are respected and loved." How much truer and beautifully bluer do our own lives become when we do that and get to hear the ancestors whisper back?